There’s No Such Thing as Stupid: Why “Intelligence” Measures the Evaluator, Not the Evaluated

The arrogance of dismissing what we fail to understand

Stupidity doesn't exist in the world. When we call a person or animal "stupid," we're revealing our own inability to recognize forms of intelligence different from our own. Every intelligence test tells us more about the evaluator than the evaluated.

The Einstein Problem: When Frameworks Determine Intelligence

Einstein takes an aptitude test in German and scores brilliantly. He takes the same test in Mandarin and fails completely. Did his intelligence change? Obviously not. But according to the test, he went from genius to incompetent based solely on which language appeared on the page.

This exposes the circular logic at the heart of all intelligence testing: we design a test, then claim it measures intelligence. But the moment we created that test, we already decided what intelligence looks like. Intelligence isn't something we can measure directly like height or temperature (American Educational Research Association et al., 1999). It's an abstract concept we invented. Every measurement requires first deciding what we think intelligence is—and that decision is saturated with the test designer's cultural assumptions, educational background, and biases.

The framework determines the result. Test designers who measure "rapid comprehension of verbal instructions in English" have built a language proficiency test disguised as an intelligence measure. It's like evaluating art exclusively through auction prices—you'd conclude classical paintings represent artistic achievement's pinnacle while missing street art, performance art, or digital media entirely. The measurement method dictates the hierarchy. Intelligence testing operates on identical logic, just dressed up in statistics.

When "Culture-Free" Tests Prove the Point

Research on supposedly "culture-free" intelligence tests reveals this problem with brutal clarity. When Moroccan children took the Raven's Coloured Progressive Matrices using British norms, up to 62.5% scored "below average" and 15.68% were classified as "intellectually impaired" (Lozano-Ruiz et al., 2021). These were healthy children. Their cognitive abilities hadn't changed. Only the measuring stick shifted. See cover image.

Michael Cole's cross-cultural research confirms: intelligence tests are "inevitably cultural devices" (Cole, 1971). Test developers sample activities that differentiate people within their own culture. A Kpelle psychologist in West Africa would create entirely different assessments than Binet did in France. What looks like cognitive deficiency is often just unfamiliarity with specific problem-solving conventions embedded in the test.

The Pet Industry's Arrogant Dismissal of Animal Intelligence

These problems become exponentially worse—and more arrogant—when we assess animal intelligence. The pet industry and animal research fields are rife with unfounded assumptions about which species are "smart" and which are "dumb." We can't ask a crow what it values or understands. So we design tests based on what we think problem-solving looks like. Then we have the audacity to conclude animals are "stupid" when they don't perform well on our human-centric measures.

Consider the famous mirror test for self-awareness. Dogs typically ignore their mirror reflection. Does this mean dogs lack self-awareness? No. It means they rely primarily on smell rather than vision to recognize individuals. The mirror provides no scent. We designed a vision-based test for a species that experiences the world primarily through olfaction. Then we concluded the species lacks self-awareness based on our framework, not theirs.

This is pure arrogance. We've mistaken our sensory experience of the world for the only valid sensory experience. Biologist Jakob von Uexküll introduced the concept of "umwelt"—the perceptual world each organism inhabits based on its sensory apparatus and cognitive structure. A tick experiences a universe consisting of just three biosemiotic signals: the smell of butyric acid from mammal skin, a temperature of 37 degrees Celsius, and texture indicating hairless skin. Everything else simply doesn't exist in the tick's umwelt.

When we test animal cognition, we're not measuring their intelligence in any universal sense. We're measuring how well they navigate tasks designed by human minds using human assumptions. We might be mistaking forms of intelligence so fundamentally different from ours for stupidity simply because they don't map onto human cognitive patterns.

Research shows that tool use receives disproportionate attention and higher citations compared to nest building, despite both requiring similar manipulative skills. Why? Anthropocentric bias drives research interest toward behaviors that appear human-like. A corvid solving a puzzle with a stick seems brilliant to us. But the intricate magnetic navigation of sea turtles or the distributed intelligence of slime molds might represent cognitive sophistication we literally cannot recognize because it's too alien to our frame of reference.

The pet industry operates on layer upon layer of these unfounded assumptions. Dogs are "smarter" than fish. Primates are "smarter" than reptiles. These hierarchies aren't based on rigorous comparative analysis. They're based on which species can perform tricks that look impressive to humans. It's evaluator arrogance dressed up as scientific fact.

Debunked Ideas Persist as "Common Knowledge"

Here's what should terrify us: even when scientific research debunks popular beliefs about intelligence, those myths persist for decades. The left-brain/right-brain personality dichotomy provides a perfect example. University of Utah neuroscientists analyzed brain scans from 1,011 people aged 7-29. They broke the brain into 7,000 regions to examine lateralization. Their finding? No evidence that individuals preferentially use left-brain or right-brain networks more often.

Creative thought activates a vast neural network across both hemispheres. Brain scans show no hemispheric preference during creative tasks. The myth originated from legitimate split-brain experiments in the 1960s by Roger Sperry. He studied patients with severed connections between hemispheres to treat epilepsy. That research was valid. But then it escaped the lab, got simplified, exaggerated, and commercialized.

People still talk about being "left-brained" or "right-brained" as established fact. They blame poor math skills or artistic ability on their "brain type." The myth persists because it's convenient. It reinforces individualism and lets people externalize perceived deficiencies. Real research showed that some functions show lateralization. Commercial distortion claimed people have personality types determined by brain dominance.

This pattern repeats constantly. Real research produces small, qualified findings under controlled conditions. Headlines transform these into revolutionary discoveries. By the time the information reaches public consciousness, it bears little resemblance to actual research. Yet these distorted versions shape how people understand themselves and others—and how they judge who is "intelligent."

The Replication Crisis: We're Measuring Noise

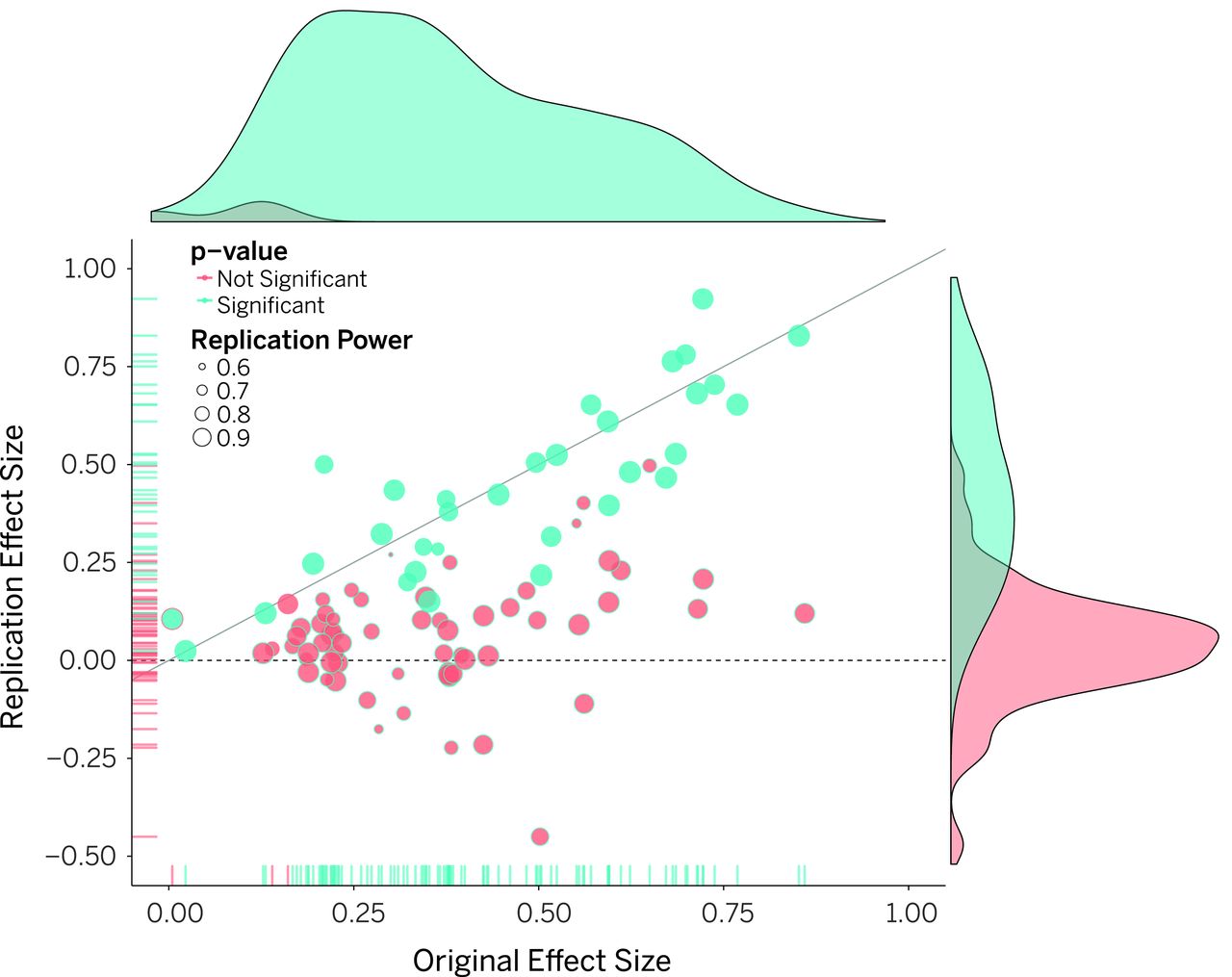

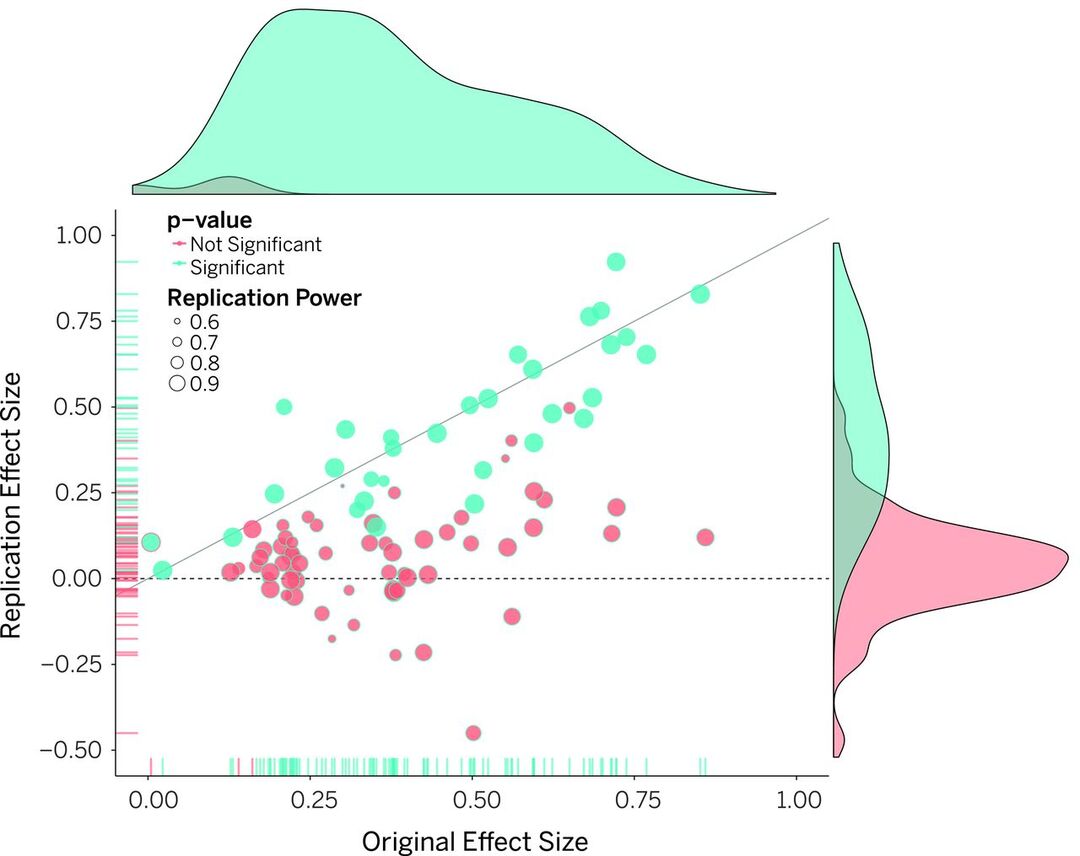

The replication crisis that emerged in the early 2010s should have shaken confidence in psychological measurement. The Reproducibility Project tried to replicate 100 studies from three leading journals. Only 36% yielded significant results, compared to 97% of originals (Nosek et al., 2022). Substantial portions of published research were documenting patterns that don't reliably exist.

One psychometrician declared that most published psychological measures are "unvalid"—their validity is unknown. Psychology faces particular challenges: measuring human behavior is less precise than measuring blood pressure. Experiments are cheap to run. Measurement is imprecise with noisy data (Bogdan, 2025). Effect sizes are smaller than researchers think. Statistical methods are often applied incorrectly.

Figure 2: Original study effect sizes plotted against replication effect sizes from 100 psychology studies. Points below the diagonal line indicate replications found smaller effects than originals. Blue indicates statistically significant results in both studies (only 36%), red indicates significance was not replicated. (Adapted from Open Science Collaboration, 2015)

The "publish or perish" culture creates situations where researcher goals conflict with scientific truth. If careers depend on novel positive findings, expect inflated effects and publication bias (Korbmacher et al., 2023). Many theories in social psychology are so loosely constructed they can be stretched to fit any result. When your theory can explain any outcome, it's not explaining anything. It's storytelling after the fact.

Every Observation Requires Interpretation

Here's the deepest problem: observations are never neutral. They're "theory-laden"—shaped by investigators' theoretical presuppositions (Hanson, 1958). There are no pure facts, only interpreted observations.

Consider a dark spot in a microscope slide. Anatomists must decide whether that spot was caused by a staining artifact or by reflected light from a significant structure. The observation is electromagnetic radiation hitting your retina. Everything else—interpreting it as a cell, artifact, or something meaningful—requires theory. Even a temperature reading of 38°C is theory-laden. The number is meaningless unless interpreted as the outcome of a measurement process (van Fraassen, 1980).

Think of it like language. You can't describe anything without words. Words carry conceptual baggage. But that doesn't make reality arbitrary. It means description is always mediated by frameworks. Same with observation—it's always mediated by theoretical frameworks. Research papers aren't "facts then theory." They're structured arguments where theory and observation are interwoven from the first sentence.

Stop Calling Things Stupid

When we call a person or animal "stupid," we're making a category error. We're dismissing unique characteristics and abilities that exist in that organism but don't register on our measurement scale. We're revealing our own limitations as evaluators, not deficiencies in the evaluated.

The most honest acknowledgment: we can measure compatibility with our frameworks. We cannot measure intelligence itself, because intelligence doesn't exist as a thing independent of the frameworks we use to conceptualize it. This isn't nihilism. It's recognizing that what we call "intelligence" says as much about us as evaluators as it does about those we evaluate.

Physical phenomena with direct measurement remain largely unaffected. Water boils at 100°C at sea level whether you're in Paris or Tokyo. But you can't stick a thermometer into "intelligence" or "creativity" or "problem-solving ability." Every measurement requires translating abstract concepts into observable behaviors. That translation is where evaluator bias floods in.

Research can be valid within its framework without being universal. A study finding "people who score high on Test X perform better at Task Y" might be perfectly replicable—within that population, using those operationalizations, in that context. Problems arise when researchers claim this reveals something fundamental about "human intelligence" rather than "performance on Test X."

Tests can never be bias-free or culturally neutral because people develop them (Ford, 2005). They reflect the developer's culture. Absolute fairness to every test-taker is impossible because tests have imperfect reliability and validity is always contextual.

The Path Forward: Epistemological Humility

The answer isn't abandoning measurement. It's acknowledging limitations honestly. It's making theoretical commitments explicit. It's testing frameworks rigorously within appropriate scope. It's recognizing that dismissing something as "stupid" reveals our evaluative limitations, not deficiencies in what we're evaluating.

Some researchers view the replication crisis as foundation for a "credibility revolution" emphasizing transparency, preregistration, and higher standards of evidence (Korbmacher et al., 2023). But transparency only helps if we're honest about what we're actually measuring.

The evaluator doesn't just influence the test. The evaluator becomes the test. Their worldview determines which questions get asked, which answers receive points, and ultimately which minds get labeled intelligent. That's not a measurement problem to be solved with better statistics. It's an epistemological reality we must acknowledge and work within.

Stupidity doesn't exist in the world. Only our limited frameworks for recognizing different forms of intelligence. When we stop mistaking our measurement tools for universal truth, we might finally see the cognitive sophistication that surrounds us—in humans who don't fit our cultural molds, in animals whose sensory worlds differ from ours, in minds that organize information in ways we haven't imagined yet. The problem was never them. It was always us.